The vaccine news that really matters

The Atlantic – October 19, 2020

Dan Barouch, MD, PhD (Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, BIDMC) discusses COVID-19 vaccine development.

Before COVID-19 upended our lives, clinical vaccine trials typically made news only when they were done—when scientists could definitively say, Yes, this one works or No, it doesn’t. These days, every step of the COVID-19 vaccine-development process comes under intense public scrutiny: This vaccine works in monkeys! It’s safe in the 45 people who have gotten it! The entire trial is on pause because one participant got sick, but we don’t know yet whether the person got a vaccine or a placebo!

“Never before have there been vaccine trials that have been followed so closely from inception to onset to conduct,” Dan Barouch, a vaccine researcher at Harvard and collaborator on Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine, says. Over the next few months, the companies behind the leading vaccine candidates will start releasing the first data from large clinical trials. Most likely, they will not be unalloyed good news or bad news. Keeping expectations measured will require understanding when a vaccine clears just one of many hurdles—it doesn’t have to be perfect, but it must be good enough.

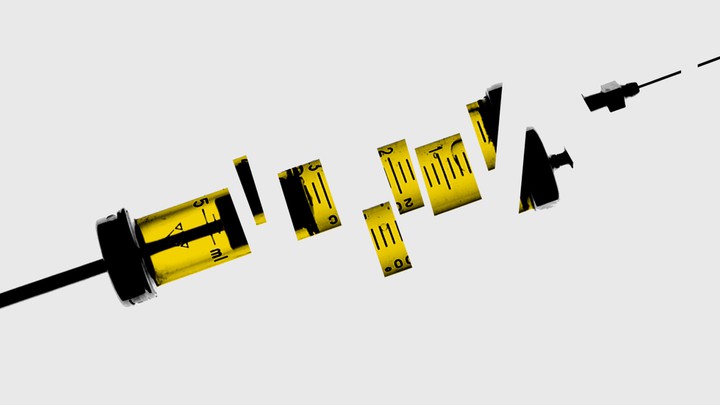

Clinical trials usually follow three phases, with the first two focused on questions of safety and dosing. By Phase 3, a vaccine should already be proven safe for most people, which leads to the key question: How well does it actually work? Five vaccines—from Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, and Novavax—have already begun or are beginning Phase 3 trials that seek to recruit tens of thousands of volunteers in the U.S.

Phase 3 trials are always large, but the ones for COVID-19 vaccines are especially so, Ruth Karron, the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Immunization Research, says. Vaccine trials depend on volunteers getting exposed to COVID-19 as they live their life: The incidence of illness in the treatment group compared with the placebo group shows how effective the vaccine is. A normal vaccine trial might recruit 3,000 to 6,000 volunteers, but could run for years. We don’t have that kind of time with COVID-19. Each trial plans for a certain number of COVID-19 infections, and to hit that number, companies can either wait a long time for fewer volunteers to get naturally infected or they can recruit lots and lots of volunteers, which is what they’ve done. “We want to be able to detect an efficacy signal as quickly as possible,” Karron says.

The public now knows exactly how many infections these COVID-19 trials are planning for—and how many would trigger an interim analysis of early data. In an unprecedented but much-applauded move, the leading vaccine companies have released detailed trial protocols. Moderna, for example, will conduct two interim analyses at about 53 and 106 infections. AstraZeneca is doing one at about 75 cases. Pfizer is doing four at 32, 62, 92, and 120 cases. “Pfizer’s, from what I can see, is the most aggressive,” Derek Lowe, a chemist who writes about drug discovery for his blog, In the Pipeline, says. Companies are not required to release interim analyses, but they might in this case, given the extraordinary public interest in a COVID-19 vaccine; promising results could also be the basis for applying for an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration. This is why Pfizer was the only company to once suggest that its vaccine might be authorized before the election—though it has since said it will wait until at least mid-November to finish collecting safety data.

Pfizer is still likely to be the first out of the gate with interim results on efficacy. “I very much hope that Pfizer does their first interim, and it kicks ass. But who knows?” Lowe says. “They also then have a better chance of doing an interim readout and having it not quite come out as strong as they want it, because they’re doing it earlier.” With such small numbers—the first interim analysis will occur after only 32 infections—it may still be unclear how well the vaccine actually protects against disease.

If most of the infections are in the placebo group—say 26 out of 32—that would suggest the vaccine is at least 76 percent effective. That’d be pretty good. But scientists have cautioned that a COVID-19 vaccine might be less effective than we’d like, based on how vaccines against respiratory viruses tend to work. The FDA has set a bar of at least 50 percent efficacy for a COVID-19 vaccine. It’ll take longer and more cases for trials to reach a conclusion if vaccine efficacy is on the lower side. So if the first interim results are a little disappointing, that “doesn’t mean this is a failed vaccine,” Lowe says. “We’re just going to keep on rolling.” We’ll have a better idea of efficacy once we’ve seen how the vaccine performs in more people.

Conversely, it shouldn’t come as a shock if some of these vaccine candidates do turn out to be ineffective. The development process from Phase 1 to 2 to 3 has gone very smoothly so far. But, in general, more than 90 percent of drugs and treatments fail, and close to 50 percent of them fail in Phase 3. Lowe says he expects COVID-19 vaccine candidates to do much better because scientists are building on research into MERS and SARS, two related coronaviruses. But the whole point of conducting clinical trials is to find out if a vaccine works, so we shouldn’t expect them all to succeed. With 46 vaccine candidates already in clinical trials around the world, scientists are optimistic that at least some will be effective.

The other big question, of course, is one of safety. The smaller Phase 1 and Phase 2 vaccine trials have so far found adverse events including fatigue, chills, headache, and pain at the injection site. But the big Phase 3 trials are meant to find rarer adverse events that might turn up in only, say, one in 10,000 people. That’s one advantage of these unusually large Phase 3 studies. Then again, volunteers might get sick for unrelated reasons, too, and any connection to the vaccine can be tricky to determine. With all the Phase 3 trials going on, “you’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people, some of whom are elderly, over a prolonged period of time,” Barouch says. “So there will be heart attacks. There will be strokes. There will be cancers. There will be neurological events.”

A serious adverse event—like a neurological disorder—triggers a study pause and a review by an independent data-and-safety-monitoring board. This board is made up of scientists who do not work for the vaccine company and are not investigators for the trial itself. First, they would “unblind,” to figure out whether the person got a vaccine or a placebo. And if the participant got the vaccine, the board might seek additional medical records and data to look for any possible link between the vaccine and the adverse event. The AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson vaccine trials are currently halted in the U.S. due to adverse events, though AstraZeneca’s has since resumed in other parts of the world. These pauses are relatively common with vaccines, which have a very high safety bar because they, unlike drugs, are given to healthy people. Normally, a pause doesn’t become public if the trial is resumed, but COVID-19 vaccines are under special scrutiny. “Hearing there is a pause means the system is working,” Karron says, because it means safety concerns are being investigated.

Recruiting large numbers of volunteers speeds up the trials significantly, but investigators will still have to wait to understand a vaccine’s long-term safety. While normal vaccine trials might run for years before going to the FDA, the agency says it will require at least two months’ worth of follow-up data before authorizing a COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use. (Emergency use authorization, or EUA, is a lower bar than formal approval.) Peter Marks, the director of the FDA division responsible for vaccines, has said that this time frame was chosen because most adverse events show up by the two-month mark. Experts agree that this is reasonable, given the pandemic, but regulators will continue monitoring the vaccine’s safety after emergency authorization and approval.

When COVID-19 vaccines are eventually given to millions of Americans, some number of extremely rare—literally one-in-a-million—events will occur. The flu vaccine, for example, is linked to one or two additional cases of a rare neurological disorder called Guillain-Barré syndrome for every 1 million doses administered. But public-health officials weigh that risk against the 12,000 to 61,000 people who die of seasonal flu every year in the U.S.

With the FDA’s two months of required safety data, mid-November is the earliest companies might seek emergency approval for a COVID-19 vaccine, assuming the required number of infections is met. The interim data in a small number of people may or may not offer clear results, but the bigger picture is worth keeping in mind: Many, many candidates are in the pipeline. The first vaccine will make news, but it might not be the most effective, the easiest to deploy, or ultimately even the most widely used.