Researchers at BIDMC and Massachusetts General Hospital published a study Thursday in the Annals of Hematology that found no evidence that blood type affects whether someone develops severe symptoms (defined as intubation or death) from a coronavirus infection.

CNN – July 16, 2020

Why do we have different blood types — and do they make us more vulnerable to Covid-19?

Most humans fall into one of four blood groups — A, B, AB or O.

Ordinarily, your blood type makes very little difference in your daily life except if you need to have a blood transfusion.

However, some studies have people wondering if blood type affects coronavirus risk. One, for instance, suggests that people with Type A may have a higher risk of catching Covid-19 and of developing severe symptoms while people with Type O blood may have a lower risk.

A study published this week counters some these early findings, a reminder that scientific discovery is an evolving process. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital and Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital published a study Thursday that found no evidence that blood type affects whether someone develops severe symptoms (defined as intubation or death) from a coronavirus infection.

Other past research indicates that certain blood groups may affect vulnerability to other diseases, including cancer.

Why they matter

Why we have blood types and what purpose they serve is still largely unknown, and very little is known about their links to viruses and disease.

Unlocking what role blood types play would potentially help scientists better understand the risk of disease for people in different blood groups.

“I think it’s fascinating, the evolutionary history, even though I don’t think we have the answer of why we have different blood types,” said Laure Segurel, a human evolutionary geneticist and a researcher at the National Museum of Natural History in France.

Blood types were discovered in 1901 by the Austrian immunologist and pathologist Dr. Karl Landsteiner, who later won a Nobel Prize for his work. Like other genetic traits, your blood type isinherited from your parents.

Prior to the discovery of blood groups, a transfusion, a now common lifesaving procedure, was a high-stakes process fraught with risk. Pioneering physician Dr. James Blundell, who worked in London in the early 1800s, gave blood transfusions to 10 of his patients — only half survived.

What he didn’t know is that humans should only get blood from certain other humans.

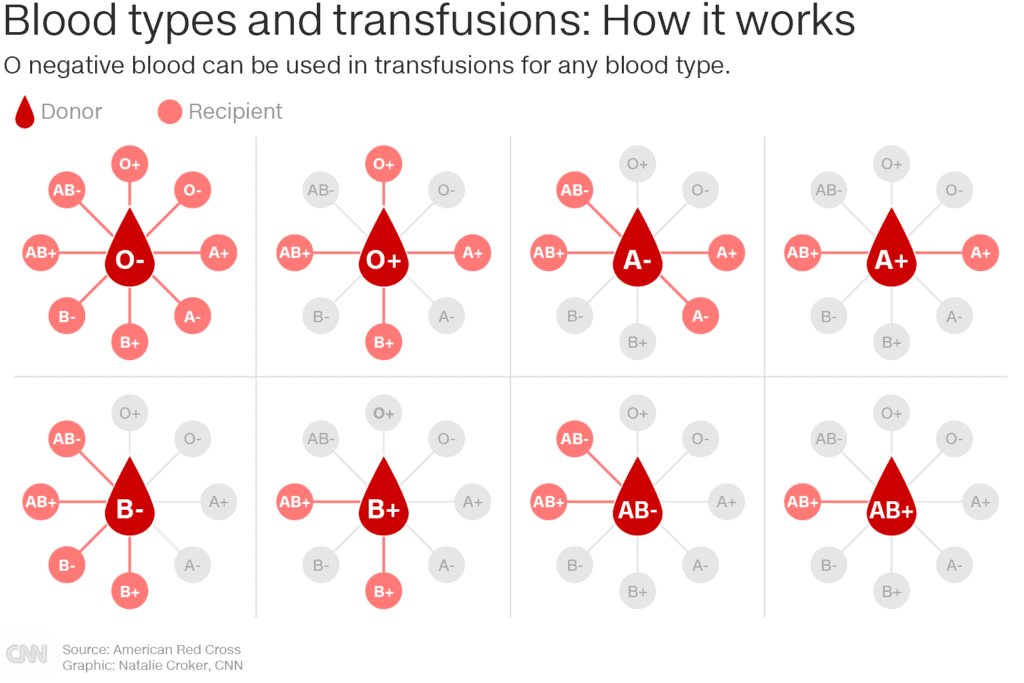

Here’s why:Your ABO blood group is identified by antibodies, part of the body’s natural defense system, and antigens, a combination of sugars and proteins that coat the surface of red blood cells. Antibodies recognize any foreign antigens and tell your immune system to destroy them. That’s why giving someone blood from the wrong group can be life-threatening.

For example, I have type A+ blood. If a doctor accidentally injected me with type B, my antibodies would reject and work to break down the foreign blood. My blood would clot as a result, disrupt my circulation and cause bleeding and difficulties breathing — and I would potentially die. But if I received type A or type O blood, I would be fine.

Your blood type is also determined by Rh status — an inherited protein found on the surface of red blood cells. If you have it, you’re positive. If you don’t, you’re negative.

Most people are Rh positive, and those people can get blood from negative or positive blood type matches. But people with Rh-negative blood typically should only get Rh-negative red blood cells (because your own antibodies may react with the incompatible donor blood cells.)

That leaves us with eight possible primary blood types, although there are a few more rare ones.

Evolutionary puzzle

It’s not just humans whohave blood types — at least 17 different kinds of primates also do, including chimpanzees and gorillas. Evolutionary biologists have found that blood types are profoundly ancient, dating back 20 million years to a distant ancestor we shared with primates.

“A lot of primate species … also have the differences of being A, being B, being AB,” Segurel said. “Whether it’s a great ape or a new world monkey, it’s quite intriguing that the differences have been found or maintained in so many different species.”

Blood types are unlikely to have lasted so long by chance. They must give us some kind of evolutionary advantage, Segurel said.

The ABO blood type gene doesn’t just influence our blood; it’s also active in a wider variety of tissues and organs, including our digestive or respiratory system, Segurel explained. This may be important when our bodies confront infection with different blood types offering us protection from different pathogens and diseases.

“The evolutionary interest of maintaining these (blood) types might not be related to their function in the blood but likely to their function in respiratory or digestive tissues,” she said. “They are the two places where you have most contact with viruses and bacteria — the places where you inhale the air and the digestive tissue.”

“If you imagine a cocktail of pathogens … there could be a cycle of sometimes B being advantageous, sometimes it’s A. Cycling through those different preferences and you end up with a population with different blood types.”

While we don’t know precisely how, Segurel said that the variation in the blood-type gene influences our susceptibility to different diseases. What we do know is that certain blood groups are more vulnerable to certain diseases.

For example, blood type B has been associated with a reduced risk of cancer; while group O has been linked to a lower risk of dying from severe malaria but appeared to be more susceptible to norovirus infection, the winter vomiting bug that also causes diarrhea.

So what about coronavirus?

A handful of studies have shown a link between blood type and the novel coronavirus, though most involved a small number of people and some were not peer reviewed.

A team of European researchers who published their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine in June found people with Type A blood had a 45% higher risk of becoming infected than people with other blood types, and people with Type O blood were just 65% as likely to become infected as people with other blood types. They studied more than 1,900 severely ill coronavirus patients in Spain and Italy, and compared them to 2,300 people who were not sick.

A similar effect for Hong Kong health care workers with blood group O was observed during the SARS outbreak, which infected 8,098 people from November 2002 to July 2003 and is from the same family of viruses.

This week’s study may counter some of that research. “We showed through a multi-institutional study that there is no reason to believe being a certain ABO blood type will lead to increased disease severity, which we defined as requiring intubation or leading to death,” said Dr. Anahita Dua of Mass General, who led the study team.

There are two hypotheses about the link between blood groups and Covid-19, said Jacques Le Pendu, research director at Inserm, a French medical research organization. One is that people with type O are less prone to coagulation problems and clotting has been a major driver of the severity of Covid-19.

He said it could also be explained by the likelihood that the virus will carry the infected person’s blood group antigen. As such, the antibodies produced by a person with blood group O might neutralize the virus when caught from a person with blood group A — similar to the rules for blood transfusions.

“However, this protection mechanism would not work in all situations. A blood group O person could infect another blood group O person for example,” he explained, adding that any protective effect is unlikely to be large and the amounts of antibodies are highly variable from person to person.

People with type A should not be alarmed, nor should people with type O relax, said Sakthivel Vaiyapuri, an associate professor in cardiovascular and venom pharmacology at the University of Readingin the UK.

Vaiyapuri, in collaboration with Thi-Qar University in Iraq, is conducting a study into the role of blood types based on data from more than 4,000 people in Iraq who had Covid-19 and 4,000 who didn’t get sick. He said that early results suggest type O might have a protective effect, but it’s not definitive. And given how very many underlying variables there are, any effect, protective or otherwise, is likely to be quite small.

For example, the idea that having type O blood is protective doesn’t match up with the pattern of Covid-19 infection in the US. Type O blood is more prevalent among African Americans, yet African Americans have experienced disproportionately high infection rates.

“Group O shouldn’t think they aren’t going to get this disease. They shouldn’t be running around everywhere and not maintain social distance, nor should group A panic,” he said.

“There’s so many underlying factors. We think of this as a respiratory virus but it’s really a whole collection of things going on that we don’t understand yet,” he said.

Research on blood types has sometimes fallen between different academic disciplines, but a better understanding of why we have different blood groups and the relationship between blood type antibodies and disease risk is likely to help us to develop vaccines and design new drugs, including for Covid-19.

How to check your blood type

There are many ways for people to find out their blood type. Individuals can get their blood drawn at a doctor’s office or they can donate their blood. At-home testing options are also available for purchase online, either in the form of finger-pricking or saliva-based testing.