New study confirms staggering racial disparities in COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts

Boston Globe – August 27, 2020

In a recent study, researchers at BIDMC and Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health quantified COVID-19′s disproportionate toll on Black and Latino communities in Massachusetts and explored the extent to which other demographic factors — including foreign-born noncitizen status, average household size, and the role of the essential worker — explain racial and ethnic gaps.

The pandemic produced a ’perfect storm’ of factors for communities of color.

A new study quantifies COVID-19′s disproportionate toll on Black and Latino communities in Massachusetts for the first time, and explores the extent to which other demographic factors — including foreign-born noncitizen status, average household size, and the role of the essential worker — explain racial and ethnic gaps.

The results, drawn from an analysis of 351 Massachusetts cities and towns, are staggering: A 10 percentage point increase in the Black population is associated with 312.3 more cases per 100,000 people. The same increase in the Latino population is associated with 258.2 more cases per 100,000.

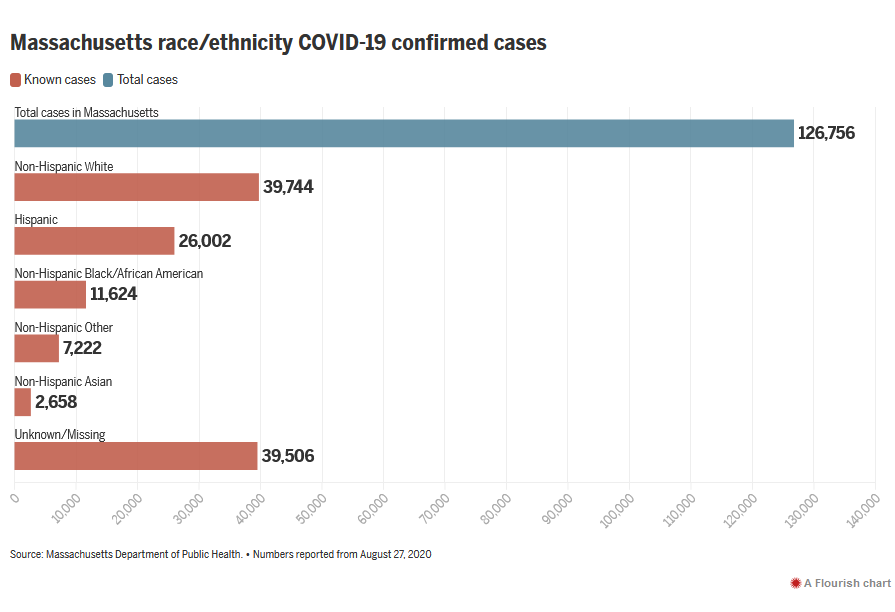

From the early days of the pandemic, Massachusetts cities with large Latino and Black populations have suffered high infection rates and death tolls. Chelsea, the city with the highest number of total cases per capita in the state, is 66.9 percent Hispanic or Latino. Of Massachusetts COVID-19 cases where the infected person’s race is known, 45.6 percent are non-Hispanic white, a group that makes up 71.1 percent of the state’s population.

Similar patterns have played out nationally. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported last week that COVID-19 infection rates are 2.8 times higher in the Hispanic or Latino and American Indian or Alaska Native populations, when compared to the rate for non-Hisanpic white people. For Black people, the case rate is 2.6 times higher and the death rate is 2.1 times higher. Case and death rates for white and Asian Americans are similar.

“We knew that these communities were being hit harder, and the question was, how much more,” said Dr. Jose Figueroa, the study’s lead researcher and an assistant professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We can now put a number to the burden on these Latino and Black communities. And it is significant.”

“This study absolutely confirms and demonstrates what we saw [in Massachusetts] and the reasons why we saw it,” said Dr. Joseph Betancourt, vice president and chief equity and inclusion officer of Massachusetts General Hospital. Betancourt said that communities of color experience a “perfect storm of conditions for the spread of coronavirus,” including less access to health care and public health information, broken trust with medical communities, environmental and public health factors that contribute to poor overall health, and — in the case of COVID-19 — work and living conditions that increase exposure to the virus.

Figueroa and his team, researchers from Harvard Chan and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, explored some of those factors. They found that higher average household size and larger shares of food service workers, foreign-born noncitizens, and non-high school graduates across cities were all independent predictors of higher COVID-19 infection rates. A city’s foreign-born noncitizen population proved to have an especially strong correlation with higher COVID-19 case rates.

Figueroa and Betancourt pointed to “public charge” standards, instituted by the Trump administration and enforced beginning in February, that allow the United States to deny visas and green cards to people who have sought aid. Those rules have been temporarily suspended during the pandemic. But immigrant advocates and public health experts widely agree that fear of “public charge” persists and, along with language barriers and fears of deportation, their specter can prevent immigrants from seeking medical care.

Risk associated with country of origin and citizenship, education, essential jobs, and household size explained Latino communities’ higher infection rates, the study found. However, those factors are not behind the disparities that Black communities see. Additional cases associated with a 10 percent increase in the Black population barely budged after researchers accounted for additional variables, dropping slightly to 307.2 cases per 100,000.

Because race is a social concept not based in biology or genetics, it does not by itself make a person more susceptible to COVID-19. Social factors other than those highlighted by the study must explain heightened exposure and infection for Black Massachusetts residents, researchers said.

Figueroa said determining “the predominant factors” is an important area for further research. Even variables that were not found to have a city-wide effect might make a difference for Black populations specifically, he said, citing Black workers’ higher-than-average use of public transportation as an example.

Some known risk factors might be better measured in Black communities using different data than researchers analyzed. Crowded housing, for example, presents in Latino communities as a higher number of people per household. But Figueroa said measuring densely populated, multifamily apartment buildings would better reflect the type of crowding Black communities are more likely to experience.

“We have to be community-specific” in our approach to public health, said Marty Martinez, Boston’s chief of health and human services. “Oftentimes we talk about Black and brown communities as if we’re one big community. In the city of Boston, that’s 55, 60 percent of the population. So we have to be alittle bit specific in thinking about individual communities and their needs.”

“We’re talking about systemic barriers [in both communities],” Martinez said. “But we have to be specific about what those gaps are . . . so that we exit COVID more equitably than we entered it.”

Though the study’s findings are specific to Massachusetts, Latino and Black communities across the United States are likely to have similar needs, Figueroa said. In fact, he said, lower household incomes and rates of insurance coverage might make disparities elsewhere in the country even more pronounced. “I think in Massachusetts we are seeing almost a potential best-case scenario,” he said.

The study concluded that “policy efforts that improve care for foreign born noncitizens, address crowded housing, and protect food-service workers” are in order. Figueroa emphasized that measures to reassure immigrants of their right to access health care are especially important.

Health care providers should see room for improvement reflected in the data, as well, said Betancourt. When faced with future health crises, he said, hospitals should consider identifying at-risk populations, conducting community outreach, and advocating for equitable health policy just as central to emergency preparedness as taking stock of bed and equipment capacity.

“This is the story not just of Massachusetts, but of the nation,” Betancourt said. “Communities of color were canaries in the coal mine here, and I just hope we have the courage to learn the lessons and not have a short memory about how we need to change our public health and health care system.”