As the pandemic stretches toward the one-year mark, with about half a million deaths in the U.S. alone, some healthcare workers are staying creative to cope with stress or to share a message of hope with their community. During the pandemic, Michael Gibson, MD (Interventional Cardiology, BIDMC) created about ten paintings, including one painting that was auctioned off to support healthcare workers.

Boston Globe – February 22, 2021

Healthcare workers are turning to art to cope. Here are some of their projects

“COVID Fatigue” is how surgeon Dr. Frank Candela titled his painting — a weary blue face enveloped in a cloud of black. During the winter COVID-19 surge in L.A., Candela sent the painting to Times health reporter Soumya Karlamangla, who tweeted: “When I asked him what inspired the image, he said, ‘my colleagues faces.’”

As the pandemic stretches toward the one-year mark, with about half a million deaths in the U.S. alone, healthcare workers are increasingly burned out and traumatized.

For some, staying creative is a form of escape, a way to cope with stress or a strategy for sharing a message of hope with their community. The Times spoke to five healthcare workers — who are also a painter, a choreographer, a photographer or an illustrator — to learn more about how the pandemic has affected their artistry.

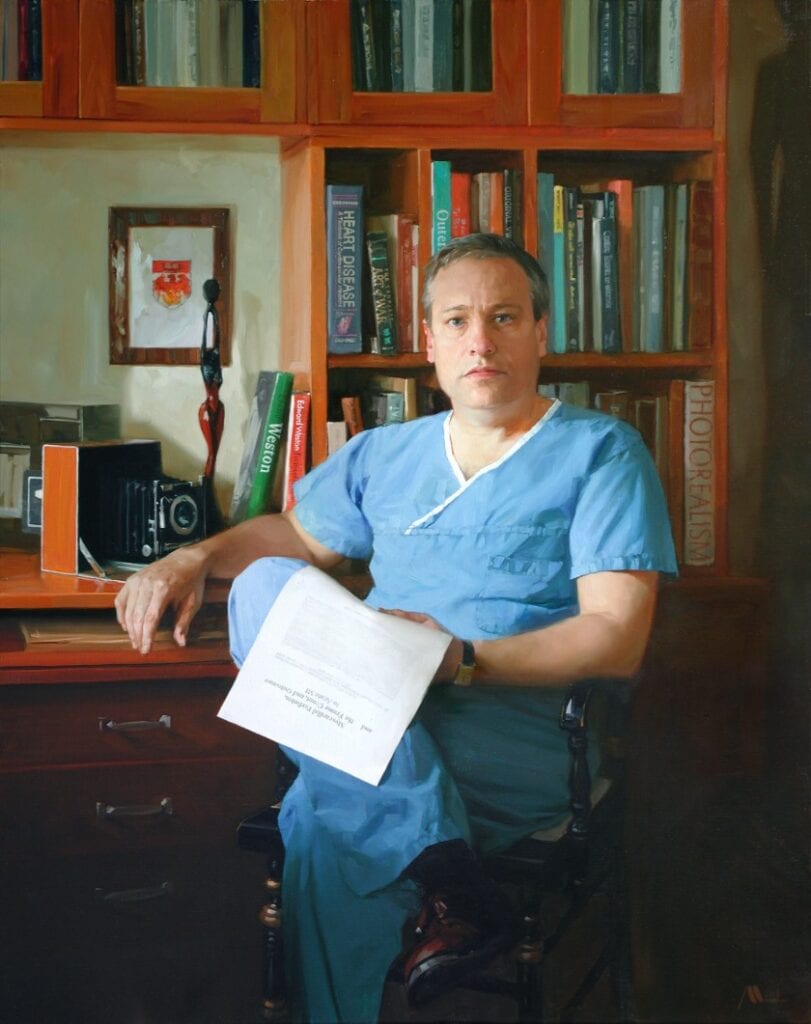

C. Michael Gibson: interventional cardiologist, researcher, educator, painter

In Dr. C. Michael Gibson’s oil painting “The Last Shift,” a line of dark, floating silhouettes drifts off into a hazy light. Gibson shared the painting, which was auctioned for $25,000 to support healthcare workers, on Twitter last March, adding: “Welcome home to all of our courageous #CoronaHeroes who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

The isolation of the pandemic has meant more time to look inward. For Gibson, “The Last Shift” is a meditation on spirituality and vulnerability, “not afraid to talk about it, knowing that so many other people were probably facing the same concerns about where’s everyone going after this. Are they going to be OK? All those issues we all struggle with.”

As a practicing physician, Gibson spends one day each week doing procedures, opening up people’s arteries. It’s a visual job, he said. “You’re looking at a screen and finding these blockages and making them better, so we’re kind of visual athletes. And being a painter has always made me a better visual athlete.”

In addition to his work as a cardiologist, researcher and educator, he paints most nights and weekends at his studio in Natick, Mass. Art is his way to communicate nonverbally and “allow a lot of all those feelings, emotions and right sided things that are all pent up in there to come out.”

During the pandemic, Gibson has created about 10 paintings. About half are directly related to the pandemic. He was particularly inspired by a nurse in a Dove commercial, struck by her exhaustion and the marks the mask left on her face. He said it captured “not just the outward appearance but the inward appearance of so many healthcare workers who’ve been traumatized by the violence.”

Other paintings have been more abstract, but still the pandemic showed up in subtle ways — like the increased use of grays, red and blues. “They’re not very happy paintings,” he said.

A recent ray of light: He helped to administer vaccines one weekend in Central Falls, R.I. “It reminded me why I was a doctor. It was a really good experience.”

G. Sofia Nelson: pulmonologist and choreographer

As a physician who specializes in the respiratory system, Dr. G. Sofia Nelson splits her time between clinic and hospital settings in Oxnard and Camarillo. When making hospital rounds before the pandemic, Nelson typically saw about 15 patients each day. But during the recent COVID-19 surge in Southern California, Nelson saw between 50 and 60 patients every day.

Nelson, 33, would often return home from work, not because she had treated every patient, but because she was exhausted. There was also triaging, she said, deciding which patients could benefit from continued treatment.

Flow arts, a form of dance that involves prop manipulation, such as hoops, or juggling, was one way Nelson coped with the stress.

“It’s been long days, but it’s very powerful having something to come home to, for which I can pretty much shut off my brain. I can just really focus on my body,” Nelson said. “The more I’m working my mind and the more I’m thinking, the harder my job becomes, the more I actually have to dance to maintain that balance.”

She’s also the director of Lumia Dance Company, which she launched in 2019 as a way to give back to the arts community. In December the company premiered its debut show virtually, “Light Through Darkness,” featuring dance, aerial arts and fire spinning — all filmed in an empty North Hollywood theater.

Nelson choreographed three dances in the show over several months, typically rehearsing on Zoom during evenings and weekends. One dance was a post-apocalyptic hoop piece about the pandemic experience, another was inspired by what she described as the government’s increased militarization and fascism, and a duet explored the pitfalls of social media.

Now that the show is over, Nelson mainly dances at home as a form of movement meditation, reaching the same type of head space many surgeons use in their practice, she said. “It’s really important that we create a culture where physicians are encouraged to have creative outlets like this. We create a society in which not just physicians, but anybody, really has that kind of opportunity.”

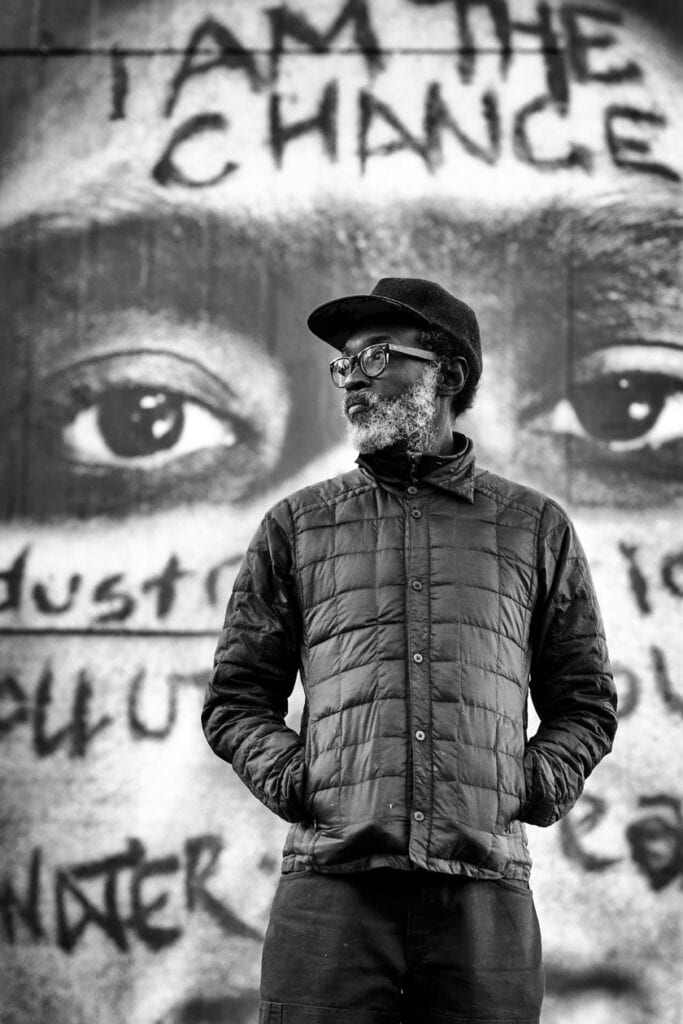

Chip Thomas: family physician and photographer

For the last 33 years, Dr. Chip Thomas has worked on the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the U.S., spanning parts of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, and also among the hardest hit by COVID-19. As a family practice physician, Thomas, 63, has treated generations of families in the area. Also a street photographer who goes by “jetsonorama,” Thomas says art and medicine go hand in hand.

“When I see people in the clinic, I’m attempting to create an environment of wellness within the individual. And when I am putting art up in the community, [I’m] reflecting the beauty of the community back to people.”

In 2009, Thomas began creating public installations of his photography, using spaces throughout the Navajo Nation as a way to share messages. Some of Thomas’ prior work focused on public health awareness, including commentary on people’s food choices.

During the pandemic, he created large-scale public service announcements posted on abandoned buildings and billboards encouraging residents to wear a mask and stay positive despite the tough times.

Last November, Thomas published a 115-page multimedia zine called “Pandemic Chronicles, Volume 1,” inviting visual artists and poets to respond to how the pandemic disproportionately affected their communities. Thomas shot much of the photography in the zine during weekends and his time off work.

One image, of an older woman and child in a masked embrace, is a family Thomas has worked with since 1987.

The young girl in the photo is about 9. “I started photographing her when she was 6 months old,” Thomas said. “One of the things I love about that image, other than the fact that they’re both wearing masks, is they’re touching. … With social distancing and the emphasis on mitigation measures, a lot of people don’t have an opportunity to touch and embrace like that.”

Thomas was recently invited to create a project funded by the United Nations, working with activists to create an art-based response on the Navajo Nation to the mental health challenges caused by the pandemic. The project’s title, “Pandemic as Portal,” is based on an essay of the same name by Indian author Arundhati Roy.

Tessa Moeller: nurse and painter