Gyongyi Szabo, MD, PhD, Chief Academic Officer, BIDMC and BILH, discusses how lab work has changed due to COVID-19. She encouraged lab members not in the lab to take advantage and “do some deep thinking.” They should ask themselves, she said, whether they’re on the right path and, if so, think about new projects, set goals for the next year, and consider where they see themselves in five years.

Harvard Gazette – July 16, 2020

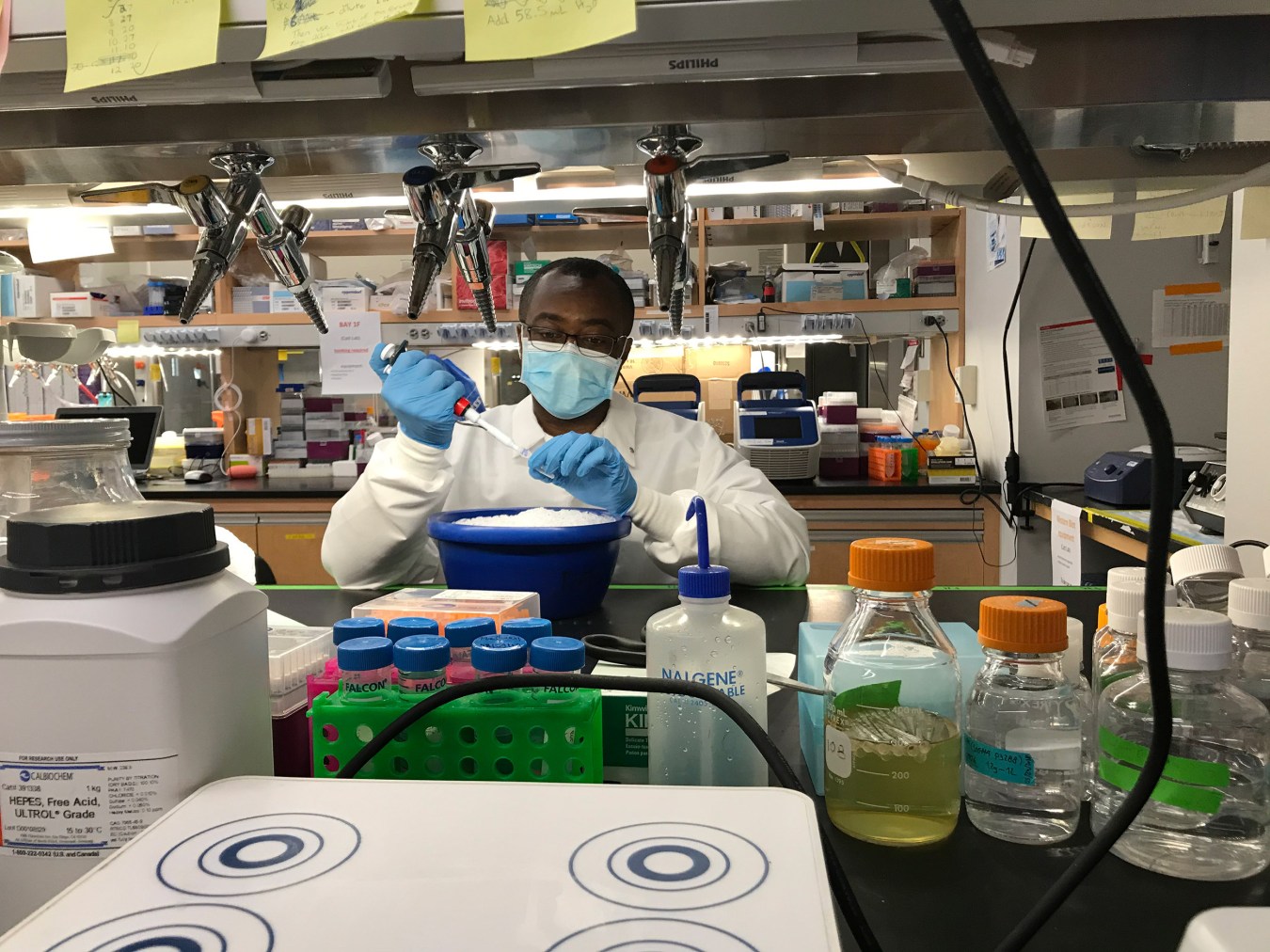

Researchers across Harvard’s Schools and affiliates settle into masked, distanced, rigidly scheduled shifts, and resume the important work they love

The worms are thawed and wiggling, the mosquitoes bred, buzzing, and adding to the other sounds of science being heard again across Harvard’s campuses and those of its affiliated hospitals.

For thousands of faculty members, postdoctoral fellows, students, research staff, and administrators, the transition from home to lab over the last few weeks is largely complete. Researchers are settling into de-densified labs with fewer colleagues, getting used to everyone being in masks, and adjusting to new routines — cleaning protocols, hand washing, traffic patterns, even guidelines for lunch — all devised with safety in mind. By now, many have had a baseline COVID-19 test and logged daily symptoms on the Crimson Clear smartphone app, which has gotten largely positive reviews. And research in the myriad areas unrelated to the pandemic is again underway.

“I have to say that even though at the beginning there were uncertainties, and there were additional guidelines almost every day, everything has gone smoothly since,” said Marina Garcia, a postdoctoral fellow and COVID safety officer in the lab of Harvard Medical School Professor of Genetics Monica Colaiacovo.

Informed by the work of the multi-institutional Laboratory Reopening Planning Committee, headed by Harvard’s Vice Provost for Research Richard McCullough, labs began reopening in early June, with a handful of individuals beginning to carry out the cleaning, signage, work-station distancing, and other steps that were required before more could return.

With Harvard-affiliated hospital representatives on the committee, McCullough said they were able to lean on the experience and insight gleaned from months of handling COVID-19 cases.

“Everybody was pretty well aligned on what had to be done,” McCullough said. “The way we looked at it is, who better to go back than people who do research? They work in a lab environment, are comfortable with PPE, and are comfortable with environmental health and safety.”

Several faculty members, fellows, and students echoed Garcia’s assessment of a largely smooth reentry. Caroline Keroack, a Ph.D. student working in the Duraisingh Lab at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said things have been easier than expected, in part because everyone is pulling together.

“I’m pretty excited to go back to work,” Keroack said. “This is actually easier than I thought it would be. We have worked really well together within our shift to manage shared equipment and space.”

In the Harvard Chan School lab of Flaminia Catteruccia, Ph.D. student Alexandra Probst echoed others in expressing gratitude for the COVID safety officers and other colleagues who came into the lab early and got things ready.

“It was definitely strange seeing my labmates with masks at first, but I think everyone adjusted to that pretty quickly,” Probst said. “Our whole lab, and particularly our COVID safety officer Jorge Santos, did a ton of work preparing for reopening so there haven’t been too many bumps since going back to the lab.”

A generally smooth reentry, however, doesn’t mean there were no difficulties at all, that scientific work wasn’t impacted, or that life is back to normal. Researchers point out that even if nothing else suffered, ongoing experiments were interrupted and three months of research time lost. In the Colaiacovo lab, a computer hard drive failed and IT support is working to restore data from a backup. The lab, which works with experimental roundworms, also lost some lines over the hiatus. Replacements have either been ordered from a strain stock center or thawed and regrown from the lab’s frozen stocks. In other labs, researchers are awaiting the resupply of personal protective equipment, since lab stocks were donated to hospitals in March, during the state’s initial COVID-19 surge.

Researchers, like most of the rest of society, are also grappling with economic uncertainty. Initial concerns have been tempered by federal grants continuing despite the recent inactivity. And industry funders, whose dollars are often disbursed as milestones are met — a potentially challenging feature during the shutdown — have been showing flexibility, according to Allison Moriarty, vice president for research administration and compliance at the Brigham.

Moriarty said that researchers and administrators are also keeping an eye on the broader pandemic. They are aware that the return to work was made possible by the low levels of disease here, but local conditions could change with cases surging nationally.

Even as researchers have successfully embraced their new normal, some chafe at the rigid shift schedules, which vary between institutions but make the loose, anytime work culture a thing of the past — and perhaps the future. Instead of working until daily goals are accomplished, labs are now run on relatively strict timetables that must be observed to allow cleaning time before the next group arrives. The shift assignments are also fixed — a way to contain any outbreaks that might occur — meaning people are not allowed to switch shifts, even if there are specific colleagues with whom they want to work.

Sarah Fortune, chair of the Harvard Chan School’s Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, said if there were one thing she could change, it would be allowing more flexibility, which she believes could be done while enforcing distancing and other safeguards. “I’m even starting to think we’ve learned from this. Maybe we can envision the labs of tomorrow.” — Nathalie Agar, associate professor of neurosurgery and of radiology at HMS

“It is sad. A lab is like a family, and we clearly have lost a lot by not being able to eat together every day or randomly have tea and start brainstorming,” Fortune said. “This is doable but not the same.”

It may be even more difficult for principal investigators like Fortune, whose guiding and administrative roles can be done remotely and so, according to reopening guidelines, should be. Nathalie Agar, associate professor of neurosurgery and of radiology at Harvard Medical School, whose Brigham and Women’s Hospital lab investigates brain tumors, said that, with space at a premium, she’s installed a refrigerator and microwave in her office to create added lunch space for lab members.

“They don’t want faculty there, so I just run central command from home,” Agar said.

Several researchers expressed confidence in their safety while at work but said their commutes were a major concern. During the shutdown several institutions eased parking restrictions, which allowed those deemed essential to drive to work. But with more returning, parking has again become scarce. Living close to campus is a boon, and several lab workers say they’ve taken to walking. Others say the subway commute — perhaps eased by widespread adoption of shift work in downtown businesses — has been better than expected.

“Everyone has been wearing face masks and maintaining social distance in all carriages,” said Maurice Itoe, who works in the Catteruccia Lab. “I work in the afternoon shift, and most often I am alone in a section of the train when heading home at night.”

While not entirely in the rear view, the COVID slowdown has not been without benefit. Desired or not, being locked out of the lab offered time to analyze existing data, write papers and grant applications, and begin dissertation drafts. Gyongyi Szabo, chief academic officer at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, whose lab remained partly open due to a mix of COVID and non-COVID work, said she encouraged lab members not at work to take advantage and “do some deep thinking.” They should ask themselves, she said, whether they’re on the right path and, if so, think about new projects, set goals for the next year, and consider where they see themselves in five years.

For the Brigham’s Agar, operating in the shutdown made her realize just how much work could be done remotely and may have provided a glimpse of the future. Agar’s work is heavily focused on data analysis derived from tissue samples of brain, breast, and prostate cancer and over the shutdown, she realized that even with a skeleton lab crew, much of their work could continue.

That’s because the mass spectrometers and other key equipment are accessible remotely, which means that as long as someone is there to physically swap out samples when needed, operating the machines and analyzing the data can be done from home. As a consequence, Agar said they were extremely busy over the shutdown.

“I have nothing to complain about,” Agar said. “I feel bad for the groups that lost animals and expensive cell lines.”

With the ability to do so much remotely, limits on the number of personnel allowed in the lab don’t pinch much now. In fact, Agar said, the shutdown made her realize that there’s another area where she might be able to find time: travel. During the shutdown, meetings she otherwise would have traveled to were swapped for videoconferences to no ill effect, and she expects that option to remain on the table in the future. Overall, Agar said, she has been getting more done in the same amount of time and the experience has made her think about whether the lab of the future might be smaller, less expensive, with more tasks done remotely.

“I’m even starting to think we’ve learned from this,” Agar said. “Maybe we can envision the labs of tomorrow.”