Eva Luo, MD, Toni Golen, MD (OBYGN, BIDMC) and Alexa Kimball, MD (Dermatology, BIDMC) write in STAT how healthcare providers must continue to play an essential role in halting the cycle of domestic abuse by continuing to screen for intimate partner violence during COVID-19 and the era of telemedicine.

STAT – July 17, 2020

Rising to the challenge of screening for intimate partner violence during Covid-19

Health care providers play an essential role in halting the cycle of intimate partner violence by asking their patients if they are experiencing domestic abuse, reviewing available prevention and referral options, and offering ongoing support. But Covid-19 is making intimate partner violence more likely even as it makes each of those steps more difficult.

Before the pandemic, intimate partner violence was already a national public health crisis. The CDC’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, updated in 2015, found that 34.6% of women and 33.6% of men have experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes. The survey also showed that 21.4% of women and 14.9% of men who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) have suffered severe physical violence by an intimate partner — like being hit with a fist or something hard, beaten, or slammed against something.

And slightly more than one-third of women in the U.S. have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner during their lifetimes.

Health care providers are usually the first professionals to offer care because a medical appointment has long been considered a private setting in which a patient could safely disclose violence and abuse. In fact, the Institute of Medicine and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend intimate partner violence screening and counseling as a core part of health visits.

But Covid-19 is changing all that.

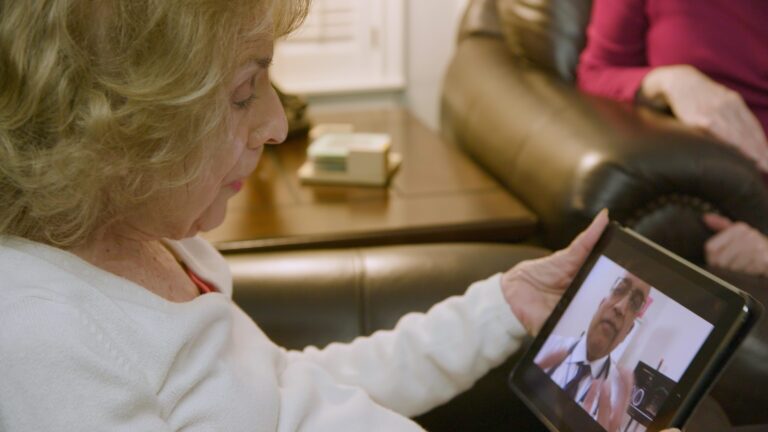

In the era of telemedicine, confidentiality cannot always be assured. Phone calls and video chats are not necessarily private, and a victim of domestic violence may not be able to voice their concerns from home, within earshot of their abuser.

Stay-at-home orders, which in some states have stretched on for months, heighten the problem because victims of intimate partner violence may be unable to leave dangerous situations. Layer on the pandemic’s other stressors — job losses, financial burdens, disconnection from community resources and support systems, and overall uncertainty — and life under quarantine can become even more perilous. Indeed, experts who work on domestic violence issues anticipate abuse to escalate, and call volumes at hotlines around the U.S. are rising.

Even the hospital setting is now less confidential.

Amid Covid-19 restrictions, labor and delivery has been one of the few hospital areas where a support person could accompany a pregnant patient during a visit to the hospital. For infection control purposes, however, the support person must stay in the room with the patient at all times. That means a health care provider cannot ask the support person to step out of the room to privately screen the patient for intimate partner violence, which is a routine part of health care delivery for all labor and delivery patients. Since it can’t be administered privately, the screening is no longer informative.

It is critical that screening for intimate partner violence continue, though the patient must be in a safe and private place before that process begins. This calls for providers to be keen and creative observers when interacting with patients virtually and in person.

When conducting telehealth visits, a health care provider needs to gauge if the patient is in a private space or is within earshot of others. That’s important not just for intimate partner violence screening, but also for asking about health concerns in general since these discussions are best done in private.

Providers can watch for nonverbal signs such as bruises, and changes in behavior such as substance use or requests for testing — which could be an opportunity for the patient to be privately evaluated in the clinic without explicitly asking for that — when assessing patients virtually and in-person. Offering patients appropriate in-person visits to the clinic or hospital for follow-up may facilitate a more private conversation or discussion about intimate partner violence and safety. And having an updated inventory of local resources and how they have changed referral channels and means of offering support during Covid-19 is also essential.

Technology provides another way to address these new challenges. Patient self-administered or computerized screenings are as effective for disclosing intimate partner violence as talking with a clinician.

At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, where we work, the OB-GYN department has taken steps to improve screening for intimate partner violence during the pandemic using an online form patients can complete on their phones or other devices to safely and confidentially report threatening situations while in the bathroom.

This project, spearheaded by Janet Guarino, an assistant nursing director for labor and delivery at BIDMC, uses a poster with instructions in several languages, including English, Spanish, and Mandarin, that is displayed in patient bathrooms. The poster includes a QR code that, when scanned with a smartphone, opens an online form that a patient can complete in seconds. Patients are instructed to close the online form once it is complete, and it is designed so no text message or other electronic trail is left on the patient’s phone.

The completed form sends an alert email to all obstetric nursing directors, who can then discreetly follow up with the patient during their hospital stay.

Intimate partner violence screening remains an essential tool for stopping the cycle of domestic abuse, and Covid-19 has changed how health care providers can help patients to find safety. In this new era of telemedicine and infection control restrictions, continued innovations can provide victims of intimate partner violence the care and support they need, perhaps now more than ever.