Dan Barouch, MD, PhD (Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, BIDMC) discusses COVID-19 vaccine development and the technology behind several leading candidates.

USA Today – November 23, 2020

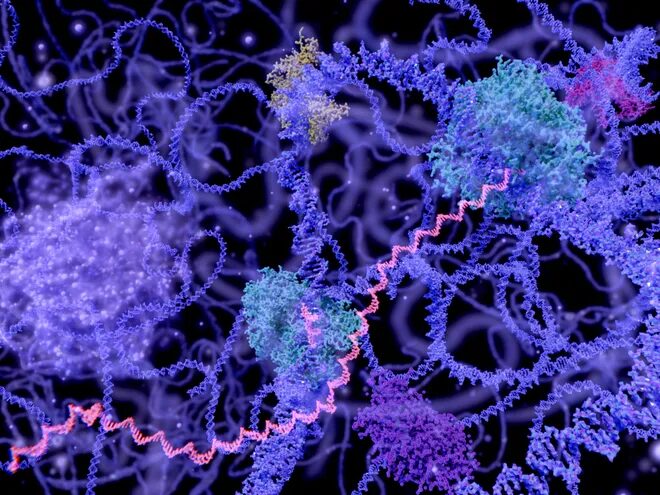

Pfizer and Moderna use mRNA in their COVID-19 vaccines. This never-before-used technology could transform how science fights diseases.

The success of two COVID-19 candidate vaccines marks a turning point in the long history of vaccines and could lead to major advances against a variety of diseases.

Vaccines developed by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are more than 95% effective against COVID-19, trials show. Both depend on a technology never before used in a commercial vaccine that could upend the way future ones are made.

This new messenger RNA technology, as well another method that depends on viruses to deliver vaccines, are transforming the field, said Brendan Wren, a professor of vaccinology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“It could be quite a new era for vaccines and vaccinology,” he said. “We seemed to move ahead in this one year 10 years.”

These technologies had advanced enough that they were ready – in time for this year’s burst of COVID-19-related funding and attention – to be proved in human trials.

It’s a silver lining of sorts to the pandemic. Without the urgency to find a solution to COVID-19, the money and the collaboration between government, academia and industry required for the breakthrough might not have come together for years, if ever.

“COVID is what made RNA jump to the head of the pack,” said Dr. Drew Weissman, a professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Though messenger RNA technology hasn’t grabbed headlines before now, a handful of researchers, including Weissman, have been working on it for decades.

“Actually, it feels like my entire life,” said Weissman, who helped launch and lead the field since the 1980s.

Messenger RNAs are part of the body’s toolkit – used to turn a DNA blueprint into the proteins needed for every cellular activity. Weissman and other researchers tried for years to get the technology to work, but every time they injected an experimental mRNA vaccine into an animal, it triggered dangerous inflammation.

However, advances in the science – some credited to Weissman and his academic colleagues, others to government scientists or those in private industry – have finally brought mRNA vaccines to the finish line.

The success serves as a reminder of the importance of basic science, said Dr. Barney Graham, a government researcher whose office has been collaborating with Moderna for nearly four years to advance their mRNA vaccine technology.

“Investment in basic science only helps,” Graham said. “Even if it looks like some arcane idea that doesn’t make sense, that kind of knowledge and basic understanding of biology and how things work are really informative to this kind of program.”

The success of the companies’ mRNA vaccines proves the technology is sound. Pfizer’s completed trial of 44,000 people and Moderna’s nearly finished trial of 30,000 found the approach to be safe, causing no major health issues, and effective, protecting more than 95% of those vaccinated.

“All the boxes have now been checked. The platform clearly works,” Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in a news conference announcing Moderna’s effectiveness results.

He said he would have been satisfied had the mRNA vaccines been 70%-75% effective.

“Our aspirations have been met, and that’s really very good news,” Fauci said. “Help is on the way.”

How mRNA vaccines work and why they do so well

Advocates say messenger RNA vaccines have several advantages over traditional technologies.

They aren’t grown in eggs or cells and don’t have to go through the arduous purification of most vaccines, said Graham, deputy director of the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

“The more you can simplify things and just use exactly what you need and not anything more, overall it makes products safer and more likely to work,” he said.

The mRNA vaccines can be developed quickly.

Moderna was ready to test its mRNA-1273 candidate vaccine in people about two months after receiving the genetic code of the virus from Chinese scientists. That’s orders of magnitude faster than any vaccine ever before.

In clinical trials, the mRNA vaccines caused temporary side effects in 80%-90% of trial participants, but they were mild: Most had sore arms or felt cruddy for a day or two. No one fell seriously ill. Though that could change when vaccines are given to billions of people, the early results suggest bad reactions will be rare.

Messenger RNA vaccines contain only a fraction of the virus, so unlike some vaccines, they can’t give people the disease they’re trying to prevent or trigger allergies to eggs or other traditional vaccine ingredients.

Most of the COVID-19 vaccines under development introduce copies of the same “spike” protein found on the surface of the virus that causes COVID-19. They train the immune system to recognize this protein and attack in case of infection. The mRNA vaccines direct the machinery of human cells to manufacture that spike protein.

The downside is mRNA molecules are fragile. To keep them from falling apart, researchers spent years figuring out how to encase the mRNAs in tiny droplets of fat.

In Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine, that fat has to stay at super-cold temperatures, so it maintains its shape and shields the mRNA.

Moderna figured out how to maintain droplets for longer at warmer temperatures, so its vaccine needs to be stored at only normal freezing temperatures, or for up to a month in a fridge.

The fat droplet boosts the effectiveness of the vaccine, turning more cells into spike-protein-producing machines, Weissman said, which may be why they proved so effective against COVID-19.

“I am incredibly enthusiastic about these results,” he said.

Messenger RNA past and promise

It took years of work for Weissman and a Penn colleague, Katalin Karikó,to find that if they swapped out one of the building blocks of RNA – called a nucleoside – not only would they solve their inflammation problem, the mRNA would make much more of the desired protein.

“We thought at that point it would be a great therapeutic,” said Weissman, whose research is funded by BioNTech.

Weissman and Karikó used their modified mRNA to make a hormone called erythropoietin, the absence of which causes a lack of red blood cells, leading to anemia.

“It worked beautifully,” Weissman said. So far, the results are confined to a lab dish, mice and macaque monkeys. Someday, he hopes to test similar approaches against diseases in people.

In their lab, Weissman and his colleagues tested experimental vaccines against about 30 diseases. “It’s looked great in just about all,” he said.

Experimental mRNA vaccines have protected mice and ferrets against all types of flu. They appeared effective against genital herpes and malaria. They produced proteins that have gone missing in a wide variety of diseases, such as cystic fibrosis.

In addition to tackling COVID-19, Moderna has been developing mRNA vaccines against infectious diseases such as Zika and chikungunya, as well as others to fight cancer.

Now that COVID-19 vaccines have proved the mRNA approach can work, there should be much more enthusiasm – and money – to pursue other mRNA vaccines and therapies.

“The potential is just enormous,” Weissman said.

Over the next few years, he and other scientists will work to reduce side effects from mRNA vaccines and therapies, while making them cheaper to manufacture, more stable at warmer temperatures and more potent – so they can hopefully be given in one dose, instead of the two shots needed against COVID-19.

“My expectation is that those practical aspects, such as the temperature storage and stability over time at different temperatures, will continue to improve moving forward,” said Dr. Dan Barouch, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston.

Barouch and others dream of a vaccine that could be dispatched within a few months of a new outbreak.

“This (pandemic) would have evolved very differently if we had been able to immunize back in March,” noted Dr. Bruce Walker, who directs the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, which focuses on immunology and vaccine development.

“As we get more experience with these vaccines and as we learn from this pandemic how to actually scale up rapidly,” he said, “I think more and more time can be shaved off.”

A year ago, people would have said getting a vaccine developed and ready for the public within a year would be impossible. But two COVID-19 vaccines are likely to receive federal approval next month, and several more aren’t far behind.

“We’ve shown that’s possible,” Walker said. “And now we have to set our aspirations even higher.”