Jeffrey Saffitz, MD, Annie Cheng, MD, and James Kirby, MD (Pathology, BIDMC)discuss the outpouring of support from the Harvard medical community that has helped them combat COVID-19.

Volunteers juice COVID testing at Beth Israel

Harvard Gazette – May 11, 2020

Hard work, new equipment, and some extra help lets the lab super-charge capacity

COVID-19 has changed the way we live. For a few, like Annie Cheng, it’s also practically changed where they live.

“I have a completely different lifestyle now,” she said. “Pretty much the lab is my home.”

Cheng, the lead technologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s molecular diagnostics lab, is among those toiling to transform it from a regular 7 a.m.‒5 p.m., five-day-a-week operation into one of New England’s foremost hospital-based testing centers for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

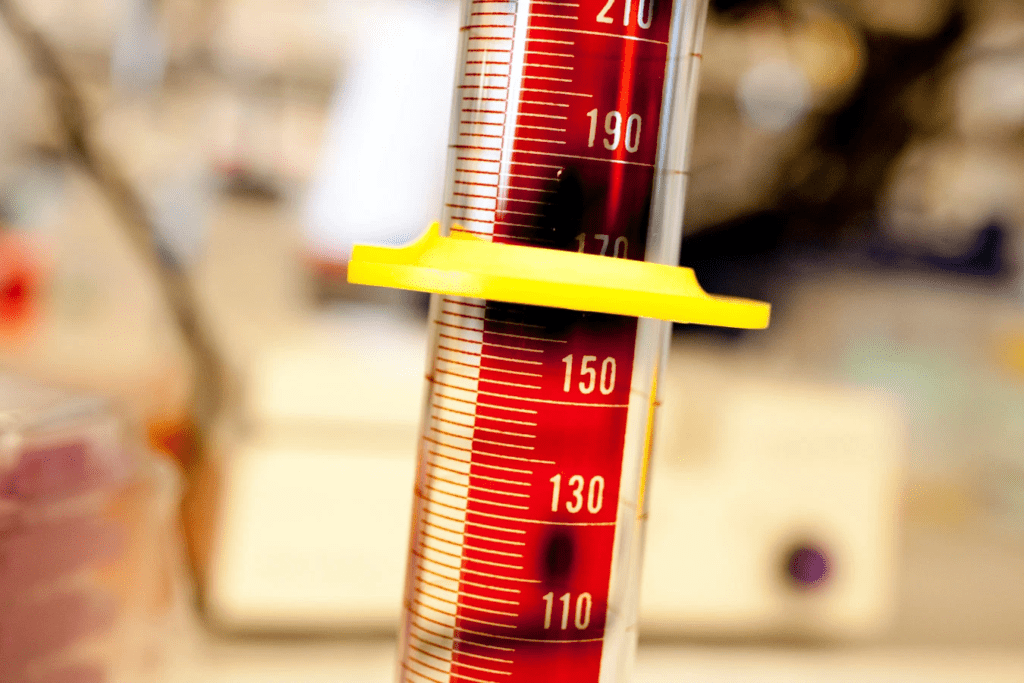

The lab has super-charged its capacity. It recently performed 1,000 tests in a day and can do as many as 1,500, an entire season’s worth of flu diagnostics. This has meant longer hours for everyone, new testing machines, and redesigned procedures to keep workers safe. But the real game-changer has been the influx of skilled volunteers from Beth Israel’s research labs, which were closed after social-distancing edicts went into effect.

“Ordinarily, we have a small number of people in our clinical lab who do this [testing] work,” said Jeffrey Saffitz, chair of Beth Israel’s Pathology Department and Mallinckrodt Professor of Pathology at Harvard Medical School (HMS). “All of the basic science laboratories at Harvard Medical School and its hospitals have been closed down, so we have this large population of research techs and postdocs who run PCR machines all the time in a research setting. We put out a call and we were gratified to have a great response. It’s a story where our community of smart, incredibly committed people will do whatever it takes to stem this terrible tragedy.”

The scramble began in mid-March, when the government allowed hospital labs to begin their own testing for SARS-CoV-2 instead of sending samples to centralized government facilities for results. The change came as U.S. disease numbers skyrocketed and what had been insistent calls for increased testing capacity rose to a shout.

Beth Israel has two main labs that do its clinical testing. Officials decided that one, the molecular diagnostics lab, equipped with high-volume machines, would handle the COVID tests. The lab, however, was initially hamstrung by a lack of test kits that would allow its machines to check samples for COVID. The shortage was met by Aldatu Biosciences, a startup with roots in Harvard’s i-lab and Pagliuca Life Lab. Soon afterward, supplies from Abbott Laboratories, which makes the machines, began to flow.

As testing rapidly ramped up, the Beth Israel lab extended its hours until midnight. That lasted about a week, Cheng said, until lab managers realized that meeting COVID-19 testing demand meant running all day, all night, and over the weekend. The lab’s staff ballooned from two to 20 as volunteers arrived. Despite the volunteers’ familiarity with the work, they had to be trained on the specific machines and on sample preparation, and brought up to speed on procedures to keep themselves and their colleagues safe — such as transporting specimens by cart, not by hand, and following the one-way traffic flows through the lab to ensure people didn’t gather in any one location.

Cheng said each day brings its own challenges. Medical emergencies are regular and require changes to testing schedules in order to provide results for specific critically ill patients. Though no technicians have been exposed on the job, one was exposed to COVID at home and spent two weeks in self-imposed quarantine. James Kirby, Beth Israel’s medical director of clinical microbiology and HMS associate professor of pathology, said once the lab’s capacity to test expanded, it became apparent there weren’t enough swabs to take samples from patients with COVID-19 symptoms or liquid media in which to transport the swabs to the lab.

In response, they set up an in-house production facility to create transport media, but then were in danger of running out of test tubes until area research labs responded with donations. To increase the supply of swabs, Kirby said, they’re evaluating 3D printed swabs they could produce on site.

“I’m amazed and proud of our lab technologists in general, and our new recruits are amazing,” Kirby said. “They enabled this high level of testing. It would have been impossible without this effort.”

Since the crisis began, Kirby said, he’s essentially been working when not eating or sleeping. Similarly, Cheng said her days have stretched from 7 a.m. until 11:30 p.m., though she’s been able to leave at 8 or 9 recently as volunteers completed training. Cheng said she’s lucky because her kids are grown, giving her the freedom to devote as much time as necessary to what she, the volunteers, and others across the hospital view as a mission.

“They know exactly what they’re doing and know what the job is,” said Erin Duffy of the volunteers. “They know they’re making an impact.” “Being able to do [work] that impacts people is a very humbling experience. It makes me feel very fortunate to have skills to be able to impact the community.” — Jihoon Lim

It was that sense of mission that prompted Duffy to find work in the lab once her job as a research assistant doing DNA and RNA analysis on mammalian tissues was halted.

“If I wasn’t doing this, I would just be sitting at home feeling like, ‘I wish I could help,’” Duffy said. “I definitely have the molecular biology skills. Those are translatable.”

Duffy describes her 3 p.m. to 11:30 p.m. shift — which sometimes lasts until 1 a.m. — as a “mad rush” to get the samples prepared and into one of the high-volume machines that can process 92 samples at a time.

“We’re really kind of running around all day,” said Duffy, who is planning to attend medical school in the fall. “It’s made me very grateful for the work those medical technologists do.”

For Jihoon Lim, part of the battle initially was just getting there. Lim, who normally works in a Beth Israel lab exploring noncoding RNA, used to take the bus to work from his home in Jamaica Plain, but now avoids both the bus and the subway. When the research labs closed on March 18, Lim stayed on for a few days with Frank Slack, the lab’s principal investigator and the Shields Warren Mallinckrodt Professor at HMS, to make sure everything was closed down and stored properly.

Lim told Slack he’d like to help with COVID testing, and Slack put him in touch with the hospital’s pathologists.

“I’m living here in Boston by myself, and I thought I could help,” Lim said. “It’s definitely a rewarding experience.”

Lim settled on riding his bike the 10 to 15 minutes from Jamaica Plain to Boston’s Longwood area for his 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. shift. Like Duffy, he often stays late before pedaling home through the darkened, depopulated streets.

Lim said his prior lab experience has been helpful, though policies and procedures are more rigid at the clinical lab, where people’s health depends on the results.

“Being able to do [work] that impacts people is a very humbling experience,” Lim said. “It makes me feel very fortunate to have skills to be able to impact the community and to help people who are waiting for results — I’m sure they’re scared, and their families are too.”

By early May, what began in mid-March as a mad scramble to get COVID-19 testing started and then rapidly — almost instantly — ramped up has become a steady grind. Though buoyed by the desire to meet COVID’s challenge, Cheng said the effort is nonetheless starting to wear on people.

“I hope this virus doesn’t last forever,” Cheng said, “because everyone is tired.”